|

The only individual in

the family who speaks Mandarin (predominantly) is my sister, and we can argue that this is an effect of the SMC.

Upon her enrolment into a primary school in 1991, the SMC was already in full-swing, having garnered a ten-year history.

A few indicators of how the SMC has affected her individual choice of language are:

1) She listens to Mandarin popular music, and the number one-rated Chinese

radio station, Yes 93.3 FM.

2)

She reads Lian He Zao Bao, the largest circulating local Mandarin newspaper.

3) She spends a disproportionate amount of her television time watching Chinese-medium programmes on Mandarin channels, namely, Channel 8 and Channel U.

Having taken these factors into consideration, one can see that the marginalization impact of the SMC on dialects

is indeed tremendous. However, while it may affect language choice on an individual level, in the case of my family, it did

not affect our language choice on a group level (since three-quarters of my family still speak Hokkien).

The SMC may not, in some examples of anomaly, bring about

a change in language choice on an individual level. The fact that my parents are not in the least affected, or even feel the

need to change their lingua franca from Hokkien to Mandarin, is a salient example. In addition, my personal preference

is to speak in English in most contexts and Hokkien at home. I find that I cannot bring myself to speak to my parents in any

other language because it would be too weird; it has to be Hokkien and nothing else. However, one must note that outside of

our family, we do engage with others (such as strangers, or when my friends visit me and speak with my parents) in Mandarin, for

the sake of communication and even social cohesion. In this sense, there is perhaps an unconscious subscription to the ideologies

of the SMC occurring simultaneously with our conscious resistance and reluctance to embrace it in entirety.

Melvin:

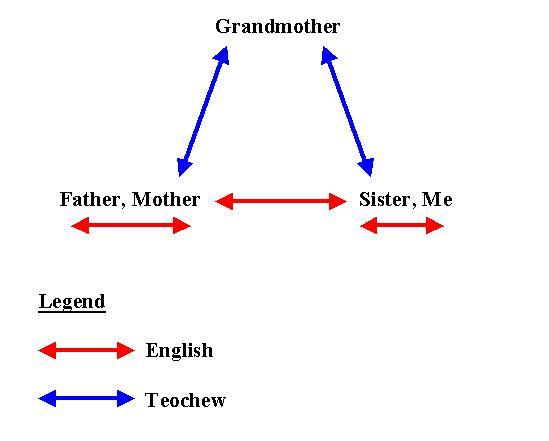

"My family consists of my parents, sister and grandmother. Other

than to my grandmother whom we speak Teochew to, my family converses solely in English."

The diagram above sums

up how the members of my family communicate linguistically.

In essence, English is

the means of communication between my parents, my sister and I.

My sister and I also communicate

with relatives of my parents generation using English.

Theoretically, although

my parents could communicate with us using Teochew, this is not practiced. One of the reasons for this is because

my sister and I only have a rudimentary grasp of the Teochew language and cannot express ourselves adequately in it. In fact,

I now speak to my grandmother in a hybrid of Teochew and Hokkien and find it hard to distinguish between the nuances of these two similar languages. In my family, Teochew

serves as a linguistic bridge between my grandmother (and members of her generation) and the next two generations (my parents

and both my sister and me).

The SMC

appears to have little effect on my family. However, the message of the SMC has been successfully conveyed to them.

Although my parents do not speak Mandarin, they have made sure that my sister and I receive additional Mandarin lessons apart

from regular Mandarin lessons in school.

However,

I am still more comfortable speaking in English and do not speak Mandarin at all unless the other party does not understand

or speak English well. In my case, the SMC does not influence language choice. Rather, my choice of English is influenced

by my lack of proficiency in both Mandarin and Teochew.

We

can see the effectiveness of the SMC through

some other examples.

For instance, many parents heeded the Government's call for them to register their children's

name in Hanyu Pinyin form. Our generation reflects this in some degree. From August 1982 to July 1984, 20.84%

of parents registered their chidren's surname and name in full Hanyu

Pinyin, 35.55% registered their chidren's surname and name in dialect with full Hanyu

Pinyin in bracket, 23.01% registered their chidren's surname in dialect

with name in Hanyu Pinyin while only 20.6% registered their children's name solely

in dialect (Lee, 1989; 42). This pinyinisation of names is reflected in our generation in one

form or another (see names in our survey marked with asterisks).

Many young people

find themselves unable to articulate more than perfunctory greetings in dialect. They are experiencing rapid attrition of

their dialects, due to the usage of English and Mandarin as a "Language of Wider Communication" (Fishman, in Bokhurst-Heng,

1998; 29) to replace terms which used to be solely communicable in dialects.

|